The Julian Calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, was the predominant calendar in the Western world for over 1600 years. It was based on a solar year of 365.25 days, with a leap year occurring every four years to account for the extra quarter day. However, this system eventually led to a slight discrepancy in the calendar year and the actual solar year.

In the Julian Calendar, a leap year is a year that is evenly divisible by four. This means that an extra day, February 29th, is added to the calendar to keep it in alignment with the solar year. While this system worked reasonably well for many centuries, the slight inaccuracies in the calculation of leap years eventually led to the need for a more precise calendar system.

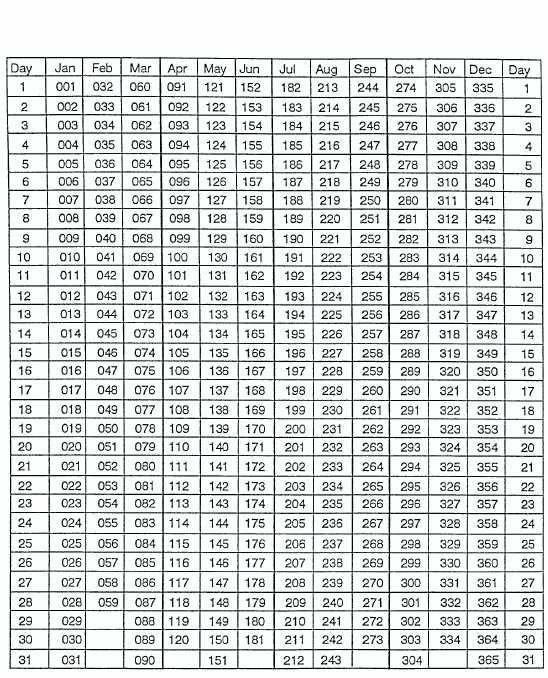

Julian Calendar Leap Year

The Transition to the Gregorian Calendar

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian Calendar to address the inaccuracies of the Julian Calendar. One of the key changes was the adjustment of the leap year rule: in the Gregorian Calendar, a year is a leap year if it is divisible by four, except for years that are divisible by 100 but not by 400. This adjustment ensures a more accurate alignment with the solar year and reduces the margin of error over time.

While the Julian Calendar is no longer used for most practical purposes, its legacy lives on in the concept of leap years and the historical development of calendar systems. Understanding the Julian Calendar and its leap year rules can provide valuable insights into the evolution of timekeeping and the complexities of measuring time in relation to astronomical phenomena.